Sitting at one of the world’s prestigious institutions—the University of Oxford, I anxiously scrolled through Instagram when I came across the horrific news of Kavin Selvaganesh's honour killing. A 25-year old software engineer from Tirunelveli district was brutally hacked to death in broad daylight for being in love with a girl from the Maravar caste, S Subashini.

The same ugly hand of caste pride took the lives of E. Ilavarasan, a Dalit youth whose marriage to a Vanniyar woman led to caste riots in November 2012 and whose body was found on a railway track in July 2013, and Gokulraj, another Dalit youth murdered for talking to a Gounder girl the following year, are a few among the many victims of caste atrocities.

Soon after this horrendous dis(honour) killing, my instagram feed was filled with the stories of condemnation and protest posters demanding justice. I had expected this. After all, most of my internet connections are committed to anti-caste politics. But, what about others? If my feed, which was curated by an instagram algorithm based on my desired interactions, what was being shown to those who take pride in their ‘dominant caste’ identity?

This question took me to a disturbing ecochamber within instagram, where the same incident was reframed not as an murder but as an act of bravery. I found several Instagram posts openly celebrating Surjith—the murderer of Kavin, also the brother of Subashini. Circulating through various caste based Instagram pages, these reels served two purposes: to glorify Surjith or elicit sympathy for him. In doing so, they sought to normalise such (dis)honour) killings, packaging the perpetrators and their violence as caste pride in bite-sized videos.

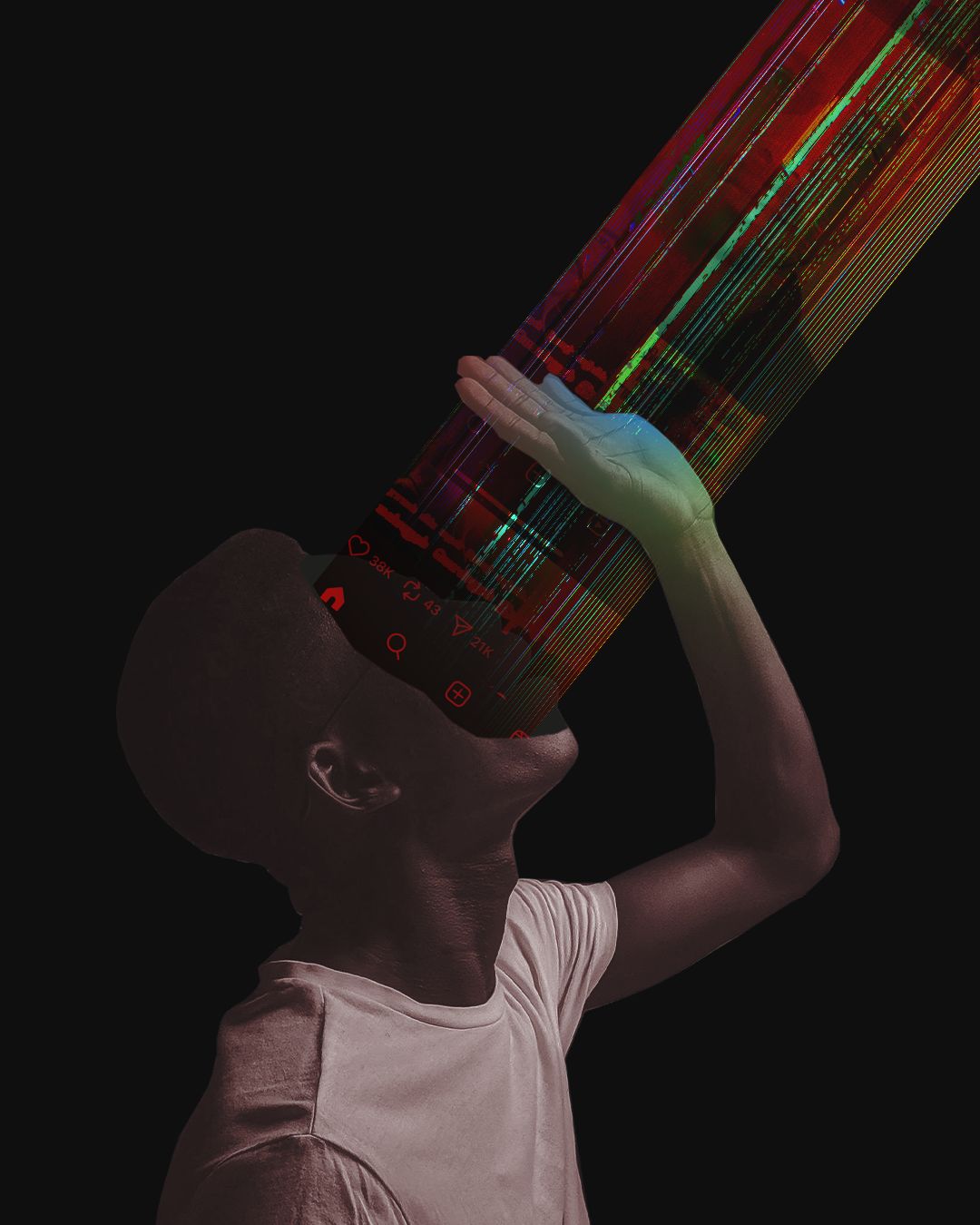

This digital glorification of caste criminals like Surjith is not an isolated incident, it reflects an alarming shift in Tamil Nadu’s online landscape. Caste pride is now being glaringly broadcasted in social media platforms like Instagram through short reels. These 30 to 60 seconds of sensory rush of bite-sized videos are becoming the tools to indoctrinate caste pride among the ‘dominant caste’ members due to the ecochamber effect of Instagram.

Due to the inadequate moderation and lack of accountability—both from social media platforms and the State—such content continues to circulate without any consequence, reinforcing caste pride and normalising violence towards Dalits.

The case of Surjith: From glorifying to victimising

On July 29—two days after Kavin's dis(honour) killing, the Instagram handle Mathan_thevar_official_72 with a following of 11.6k, posted a reel in collaboration with five other Thevar caste Instagram pages. The reel featured a photo of Surjith with Tirunelveli Railway Station board seeped in blood-red-filters, accompanied by a Tamil movie song. The caption read: In the path of Royal King Madhan Thevar, Land and Women both are important. This was one of the first reels in instagram that portrayed Surjith in the positive light.

Similarly, the next day, the same account posted another reel—this time with a rapid slideshow of Surjith’s photos, syncing with a Tamil movie dialogue. The caption read: Surjith Pandian, the Maravan who protected the honor. With its slick edit, and catchy background score, the reel cast him as a caste hero, romanticizing and glorifying caste masculinity.

When these reels started getting negative attention, the handlers of the page quickly disabled the comments section. Moving on from the hero narrative, they sought to evoke sympathy for Surjith. One reel, featuring photos of him holding the trophies, played a dramatic Tamil song in the background over the caption: Why did you hurry, brother? They also posted another reel on the same day following the same template: Sympathy for Surjith.

From a caste hero who sacrificed his life to protect the honor of the Maravar community, Surjith, now has turned into an accomplished athlete who did the murder out of the protection for his sister and family. On this logic, he becomes a victim of circumstances who needs sympathy for his actions. After this, several instagram pages started circulating these reels, manufacturing a narrative in support for him. (Currently, most of the above-mentioned reels were removed, Thanks to Instagram, however it served the purpose at that time.)

Digitisation of Caste pride

It is not the first time the convicted murderer was portrayed as a caste hero on social media platforms. Earlier this year, on March 25, when Yuvaraj, a primary convict in the Gokulraj’s honor killing was paroled for his family function, several reels surfaced in social media celebrating his release. Similarly, a ‘dominant caste’ character Faahad Faasil, from the 2023 tamil movie Maamannan, was celebrated, despite him being overtly casteist and has committed many crimes.

This overwhelming celebration of these individuals in digital spaces —fictional or real—is rooted in showcasing caste pride and hatred towards Dalits. Because, for ‘dominant caste’ groups in Tamil Nadu such as Thevars and Vanniyars, the construction and performance of caste pride is central to asserting their position and dominance in the society. Through the complex interaction of politics of martial symbolism, land ownership, controlling women's sexuality, and political assertions, they produce caste pride, which is invariably linked in cultivating hatred for Dalit.

Previously, caste associations meetings and commemorative events acted as a major channel for producing caste pride. For instance, Professor. Karthikeyan Damodaran’s work on commemorative events in southern Tamil Nadu reveals how caste pride is displayed by the Thevar caste group through the public processions. Similarly, in Northern Tamil Nadu, Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK) - a political party has routinely invoked the rhetoric of honour and bravery in their political meetings to consolidate Vanniyar's vote bank.

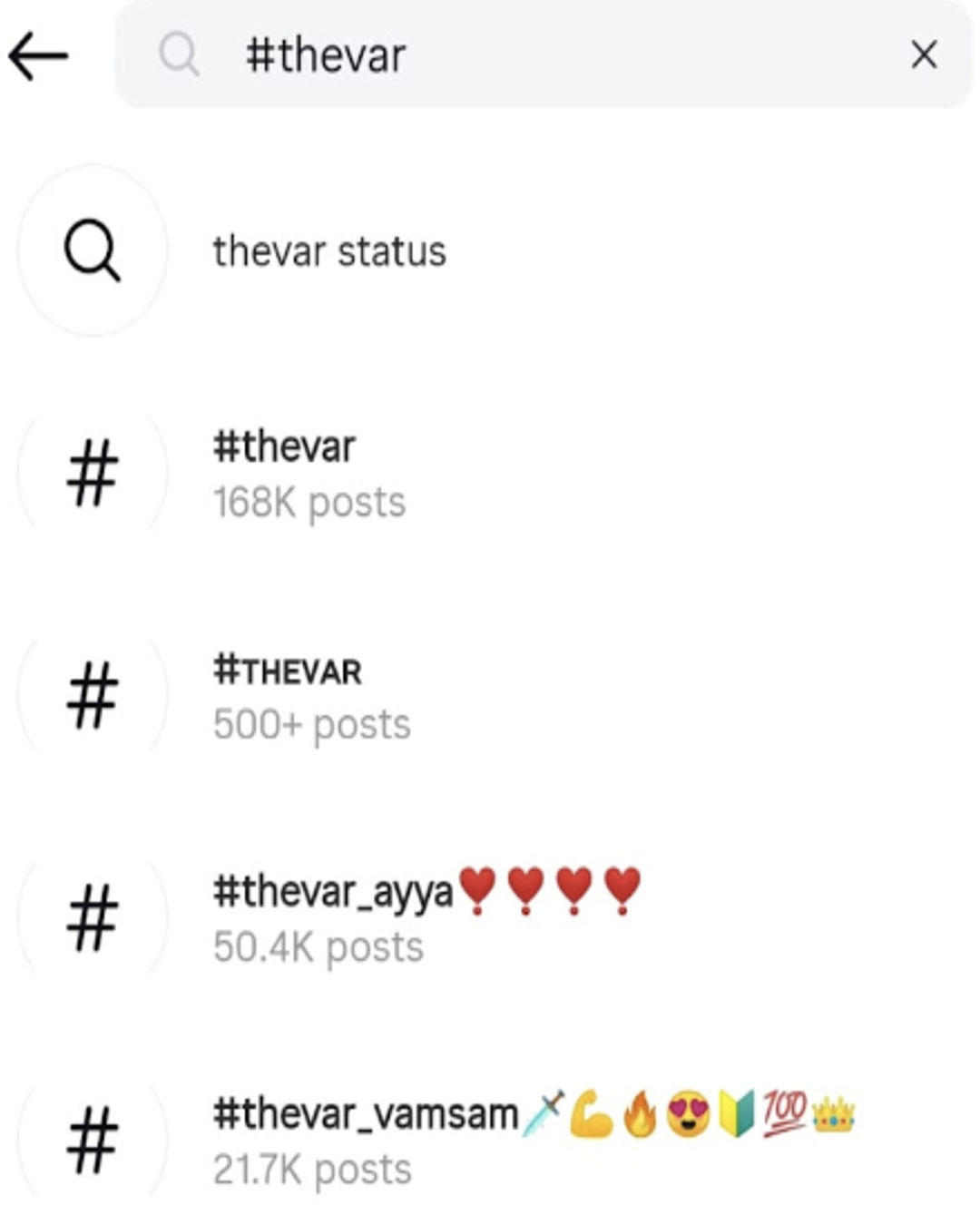

However, the advent of digital media has provided ‘dominant caste’ groups with a new channel to connect across geographies and display their caste supremacy. A simple search on Instagram using any ‘dominant caste’ name reveals the massive volume of content posted daily for consumption within their own caste networks. For instance, typing #Thevar—a dominant caste group—into the search box shows the sheer number of posts published under that hashtag.

Most of these reels invariably are tied to showcase the dominant caste supremacy, thereby triggering social division based on caste. The local caste politicians, caste party meetings and rallies, village festivals, or sometimes just a group of men enacting hypermasculinity through staged photographs with swords. For instance, a reel posted by an instagram account #sivagangai_seemaiyar shows a local Konar caste leader advising his fellow caste members that there should not be any news of our fellow being beaten by ‘others (castes)’. With the right mixture of audio-video material, these reels achieve a caste aesthetic that glamorizes and reproduces caste pride in digital media.

A dangerous trend

This digitisation of caste pride, especially of the dominant caste groups through the short reels in instagram raises serious concern, and needs to be called out urgently.

Firstly, it reproduces dominant caste supremacy in the digital space. Shreetti Shubham in her paper “Caste and Digital sphere” reveals that Upper castes perform caste superiority through anti-reservation debates, anti SC/ST acts and casteist slurs. Similarly, the dominant caste groups in Tamil Nadu produce caste supremacy by producing and engaging with the contents that often celebrate dominant caste icons, their cultural markers and glorified medieval history. Through this, they indoctrinate a particular kind of social and cultural history that naturalises their superiority and hatred towards dalits.

Secondly, the design of the instagram provides a conductive environment for the creation of caste ecochambers. Surjadeep Dutta and others, argue in their paper, “Breaking the bubble” how instagram traps their users into eco-chambers. Through the caste and region specific hashtags, the caste based Instagram pages target and curate their contents to a particular audience. Similarly, features like ‘explore’ tab further enable the user to identify and engage with caste-specific content. Due to this, caste ecochambers are created within instagram, where the users are exposed to analogous views, influencing their political and social opinions.

Thirdly, due to the eco-chamber effect, the ‘dominant caste’ users who are trapped in these algorithmic cycles are exposed to mis and dis(information), both instantly and across geographies. During caste atrocities events towards Dalits, these organised instagram networks are activated to post unverified claims and twisted facts distort the public narrative. In the case of Kavin’s honor killing, as we have seen, there was an organised attempt from many of these caste based insta pages to shift the public sympathy towards the murderer Surjith.

Why is no one watching?

There is a huge increase of the caste-pride coded contents in the social media platforms in the recent years. Under this unprecedented reel culture, it is the responsibility of State governments and International social media platforms to provide a safe space for all humans to rightly fully exist in the digital spaces without getting discriminated against. Most of the caste-pride coded contents glorify violence, which needs urgent attention.

While such reels are often published across all social media platforms, Instagram and Facebook have a large market for such reels because of the poor content moderation and inadequate accountability mechanisms. The current version of the meta guidelines on “Hateful conduct” has included “caste” as a protected category and prohibits insults based on it, however, enforcement of these guidelines remains highly questionable. For instance, Subramanian, a resident of Tirunelveli district said that despite reporting many of the caste based reels that induces violence, nothing has been taken down by the platform, reflecting the platform’s poor moderation system.

This is mainly due to the absence of contextual understanding for the definition of “Hate”. Because of the lack of regional and language sensibility of these platforms, most of the times the casteist terms and abuses are not captured by the AI tools developed to curb hate towards marginalised caste groups. These platforms should seriously implement the recommendations of the report published by the Center for Internet and Society in 2021 to adopt “robust and contextual definitions of Hate speech”.

Similarly, the state government should actively devise tools and strategies to monitor Hate content in the digital platforms. Recently, the cyber crime police and social media cell has arrested the Hatemongers, however, there needs to be more sustained long term efforts to address this problem. The caste pride coded reels is deeply seeped in the online presence of dominant castes groups. Therefore, beyond monitoring, there is a need for systematic research into the online culture of casteism, accompanied by actionable recommendations.

Alongside the much required legislation addressing the honour killings, there is also a pressing need for legislation for Hate speech to curb the casteism in the digital (and physical) spaces. As Devanshu Sajlan points out in his paper “Hate Speech against Dalits on Social Media”, the SC/ST atrocities Act can be invoked in cases of online hate speech, only when public order is directly threatened. This leaves a significant gap in the legal safeguards, allowing casteist speech—especially in online spaces—to proliferate without consequence.

Concluding, if we, as a society, are not alarmed by the algorithms of social media platforms, we risk enabling the creation of tightly knit caste echo chambers in digital space where casteism, hate speech, and caste violence will not only flourish but become normalized.

Reference:

- Damni Kain, Shivangi Narayan, Torsha Sarkar and Gurshabad Grover Online caste-hate speech: Pervasive discrimination and humiliation on social media

https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/online_caste-hate_speech.pdf - Sukshma Ramakrishnan, Cops hunt down those behind casteist posts

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/madurai/cops-hunt-down-those-behind-casteist-posts/articleshow/123150365.cms?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Roy Anto

Roy is an anthropologist and urban practitioner. He recently finished his MSc in Modern South Asian Studies from the University of Oxford. His academic interest lies in exploring the reproduction of caste and casteism in contemporary society. Currently, he works on a research project to understand caste violence against Dalit christians.