Written by Varsha Prakash (originally published in Hindi by The Third Eye, Nirantar Trust: ("किस बच्चे ने कास्ट सर्टिफिकेट अभी तक जमा नहीं कराया है." - द थर्ड आई))

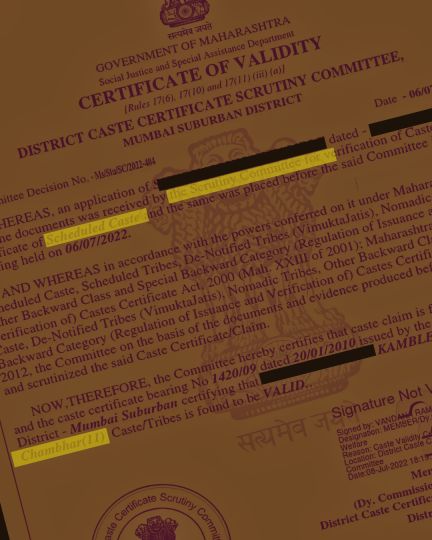

Which students have not yet submitted their caste certificates?

By Varsha Prakash

Written by Varsha Prakash (originally published in Hindi by The Third Eye, Nirantar Trust: ("किस बच्चे ने कास्ट सर्टिफिकेट अभी तक जमा नहीं कराया है." - द थर्ड आई))

Varsha Prakash

This article is written by Varsha Prakash and translated into English by Arjun. Varsha is a Dalit Hindi writer, translator, and educator with an M.A. in Political Science from Jamia Millia Islamia and a Master's in Education from the University of Delhi. Her work focuses on Dalit discourse and history, intersectional gender sensitivity, and education. In 2024, she received the Laadli Media Award for Gender Sensitivity for her writing on the experiences of Dalit women in inter-caste relationships. Arjun is an engineer, technical artist, educator, and musician based in Stuttgart, Germany. He is a founding member of the emerging initiative Samaveshi Chaupal, and an aspiring writer and translator. His work is grounded in a commitment to social and climate justice, caste abolition, radical diversity, and ethical practices in STE(A)M fields.

Enjoyed this article?

Share it with your friends and colleagues!