Early 19th Century Transformation

The Macaulay Debate

The Orientalists found Sanskrit and Arabic to be better adapted to spreading higher education including European science and philosophy along with Indian knowledge systems. The early 19th century saw the establishment of Calcutta Sanskrit College and Madrasa for this purpose.

Educational Reform and Societies

While English was not supported by the Orientalists in the Bengal government, CSBS was much more enthusiastic towards higher education in English as a way to create a distinct Hindu cultural identity for the Bhadralok.

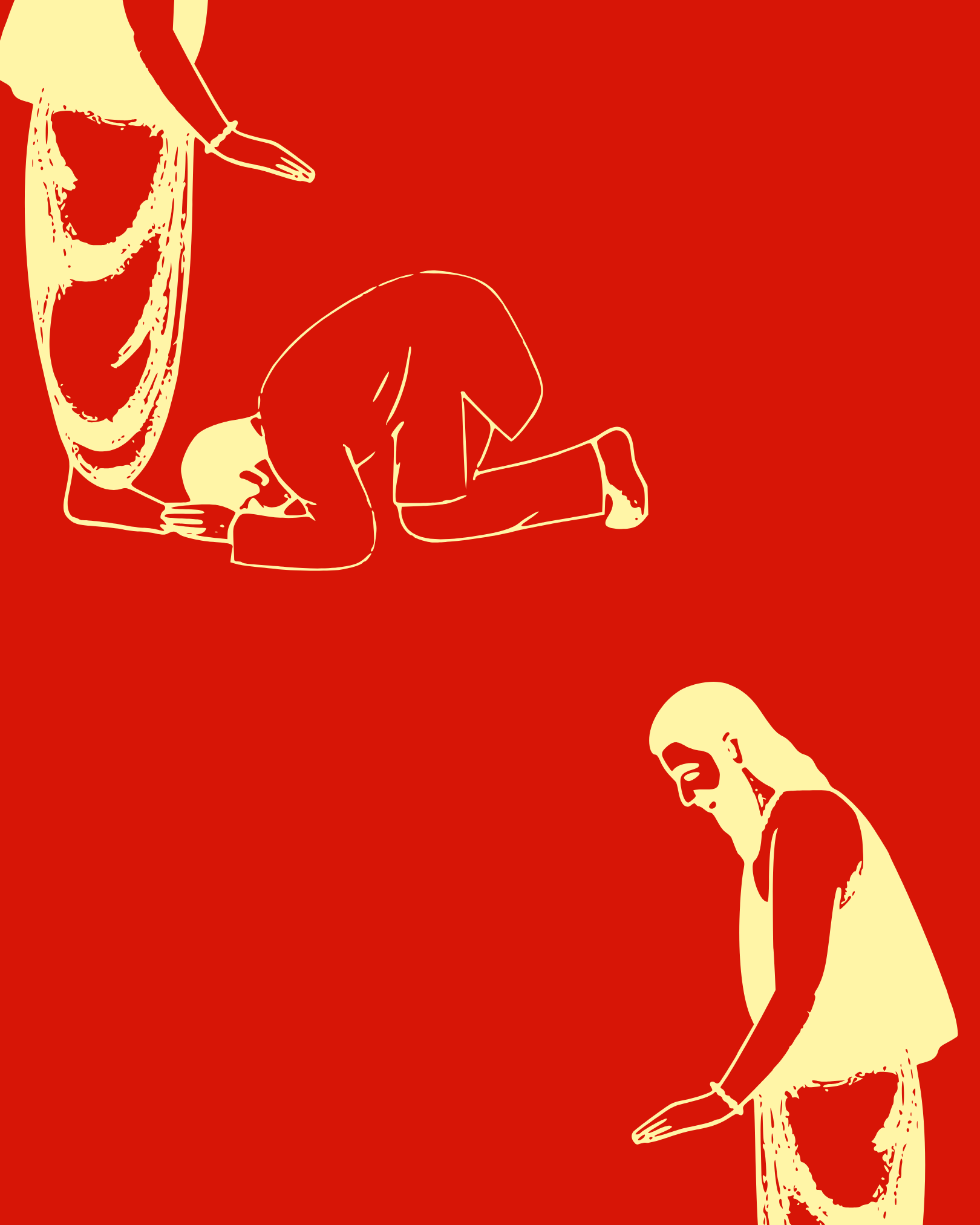

Institutional Exclusion

The caste hierarchies were reformulated in the modern educational domain. The practice of differentiated education was cemented with the policy guidelines of 1854, famously called the Wood's Despatch, which led to the establishment of the first three universities in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras with affiliated colleges.

The grant-in-aid system constituted 50% funding from the state and the other half from private entities. However, how could marginalised sections raise 50% of the amount or procure resources equalling such? Such lack in the educational domain also led to a limited number of people – upper castes – having opportunities to pursue teaching or other occupations that required high levels of education.