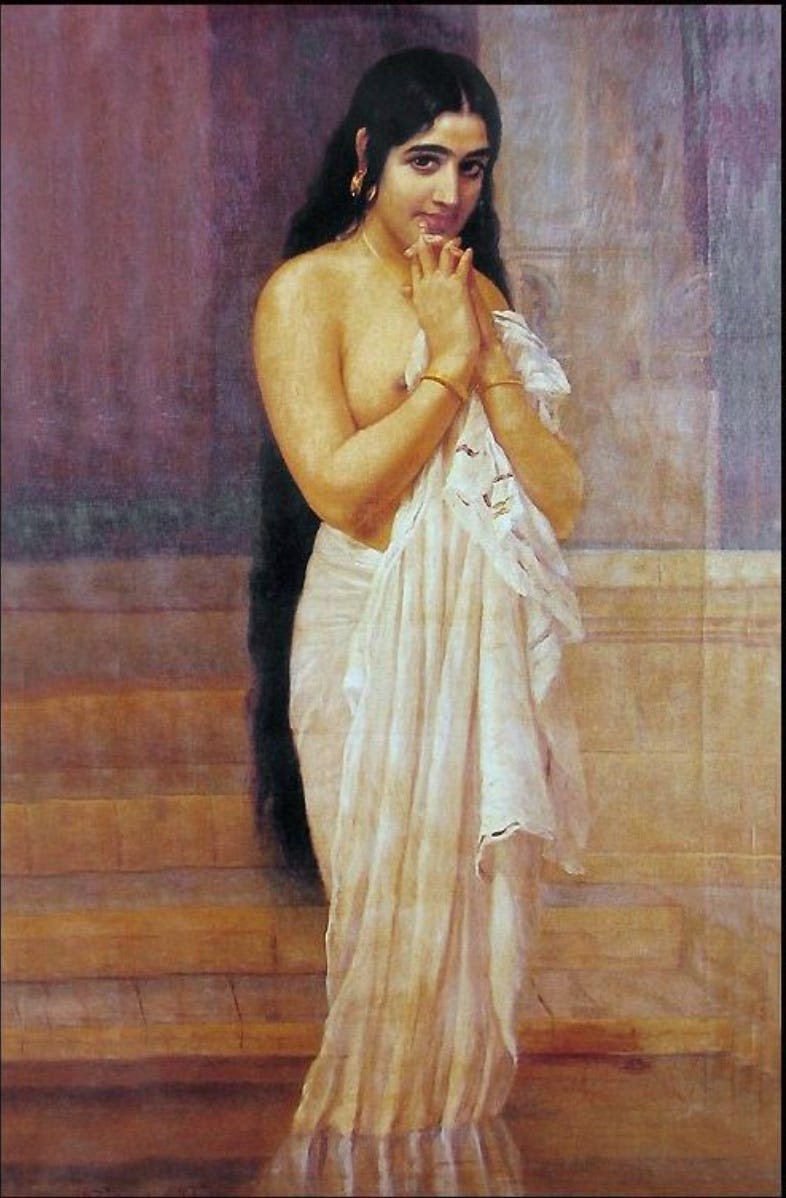

Fresh from Bath, by Ravi Varma

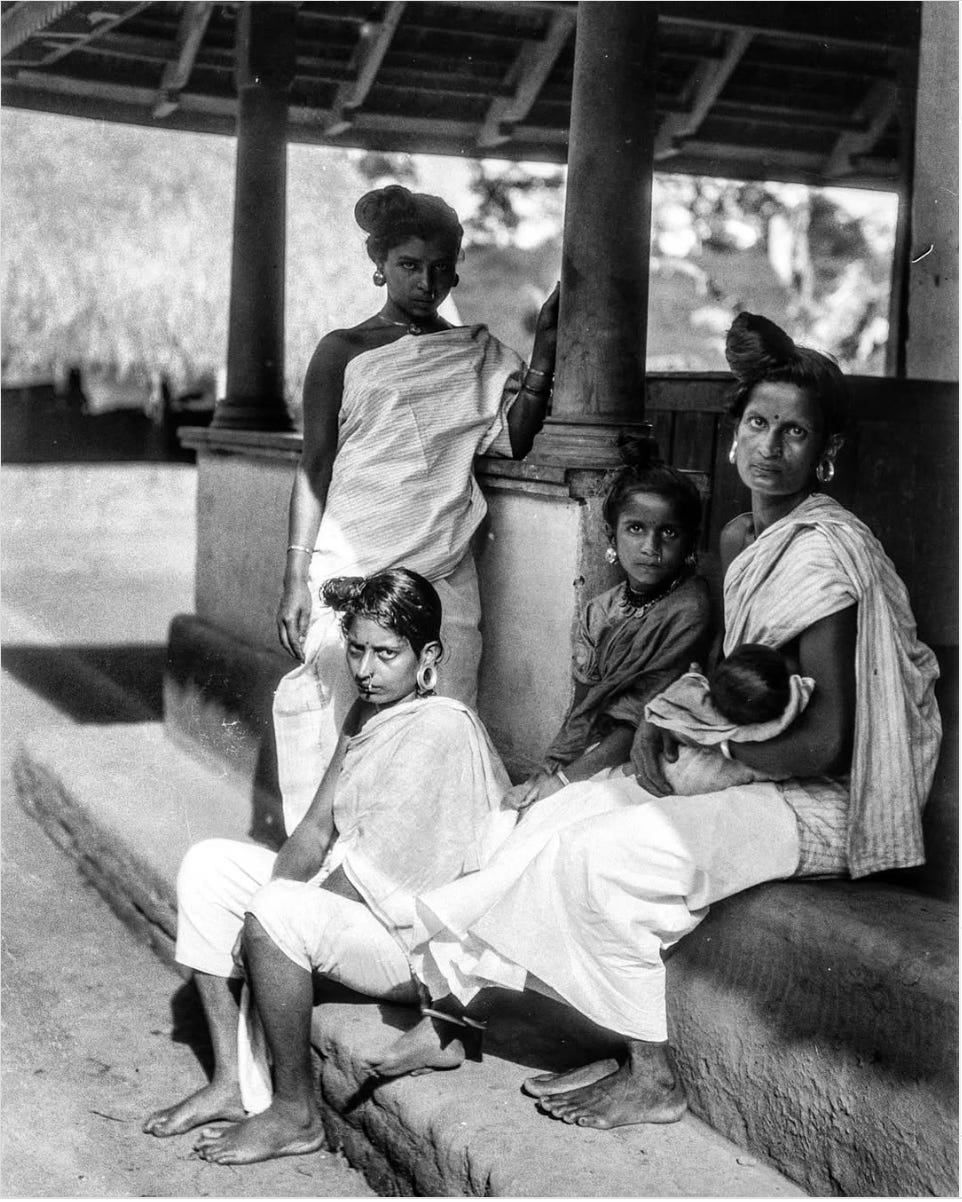

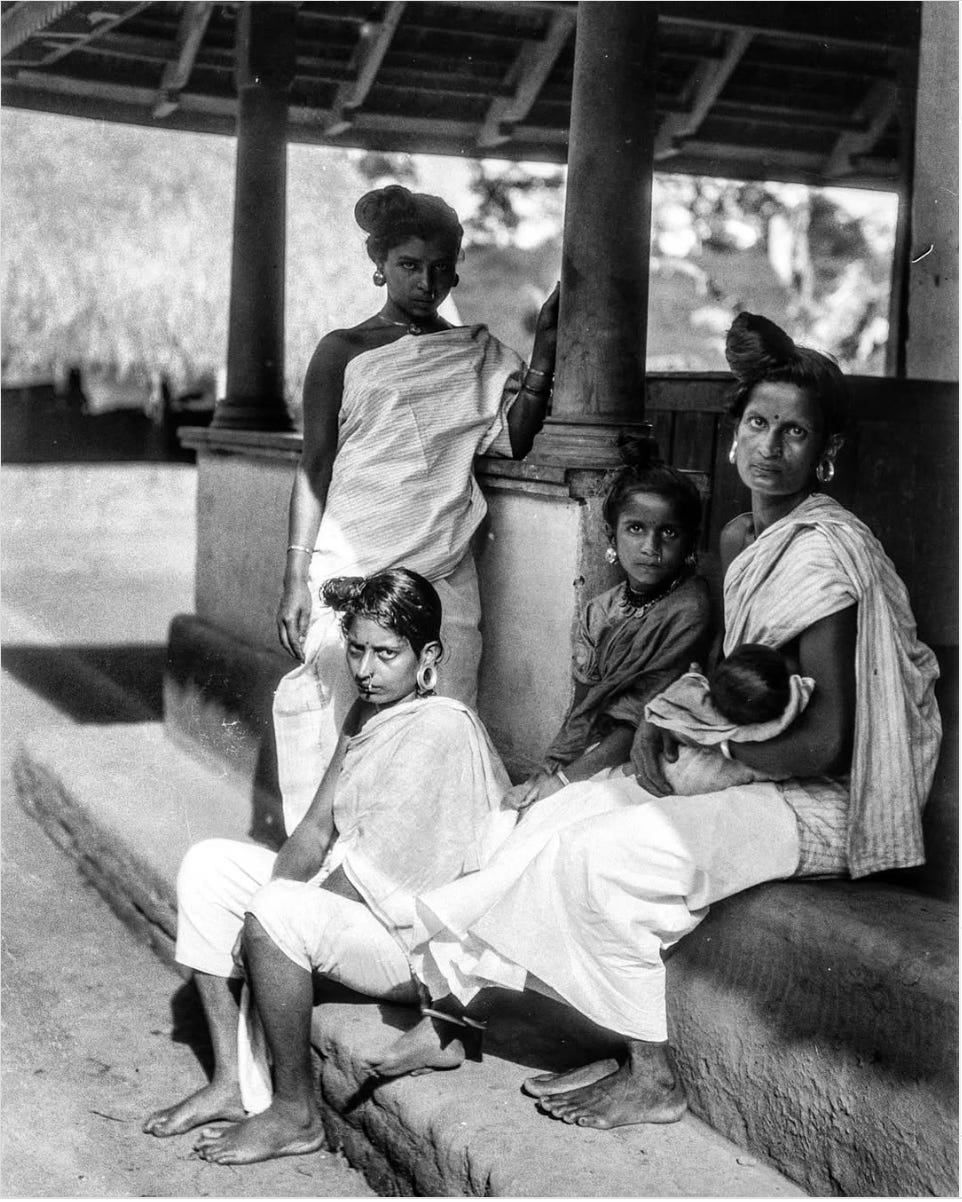

Group of Nair women photographed by Egon von Eickstedt, 1920s, Malabar.

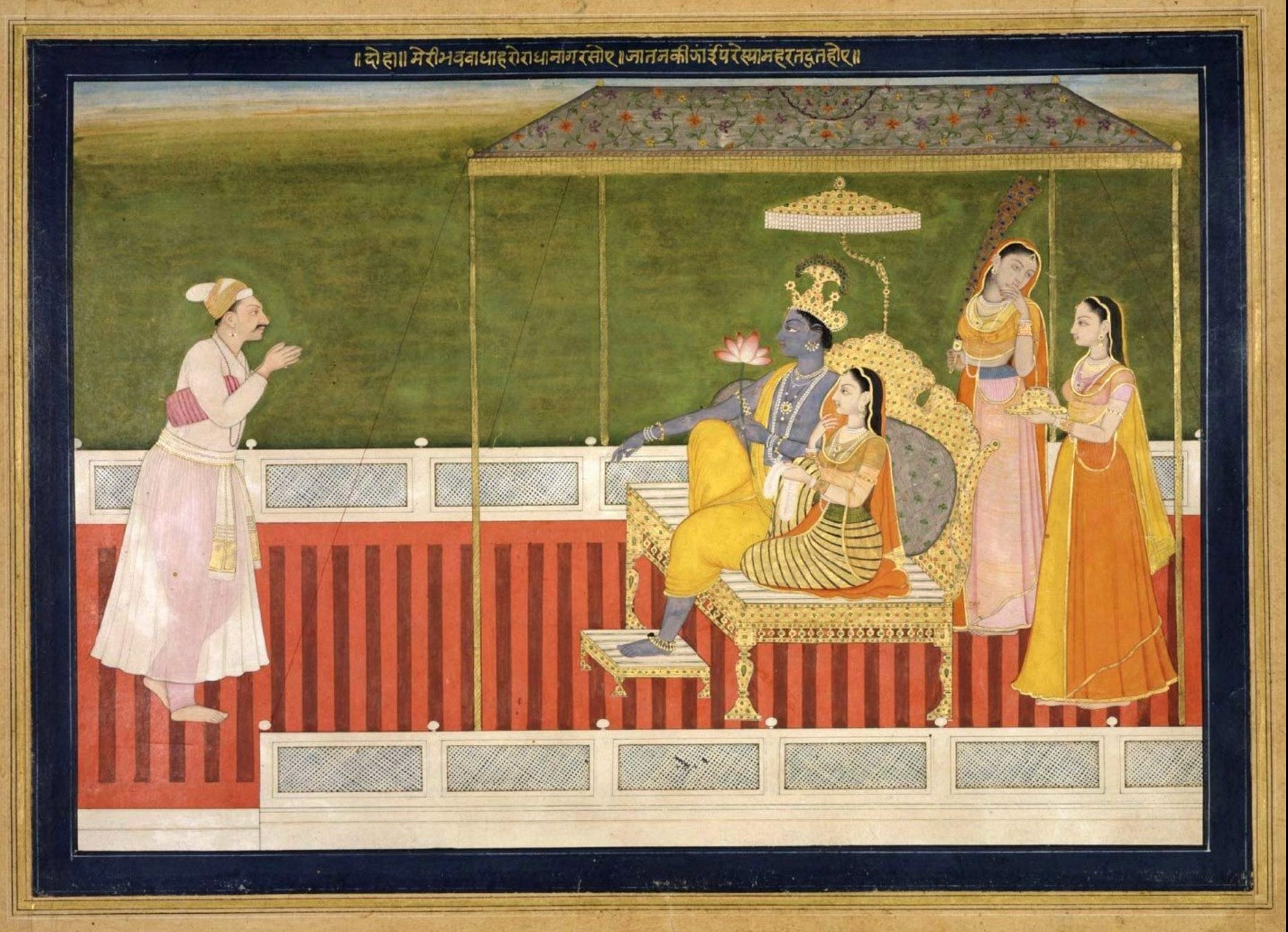

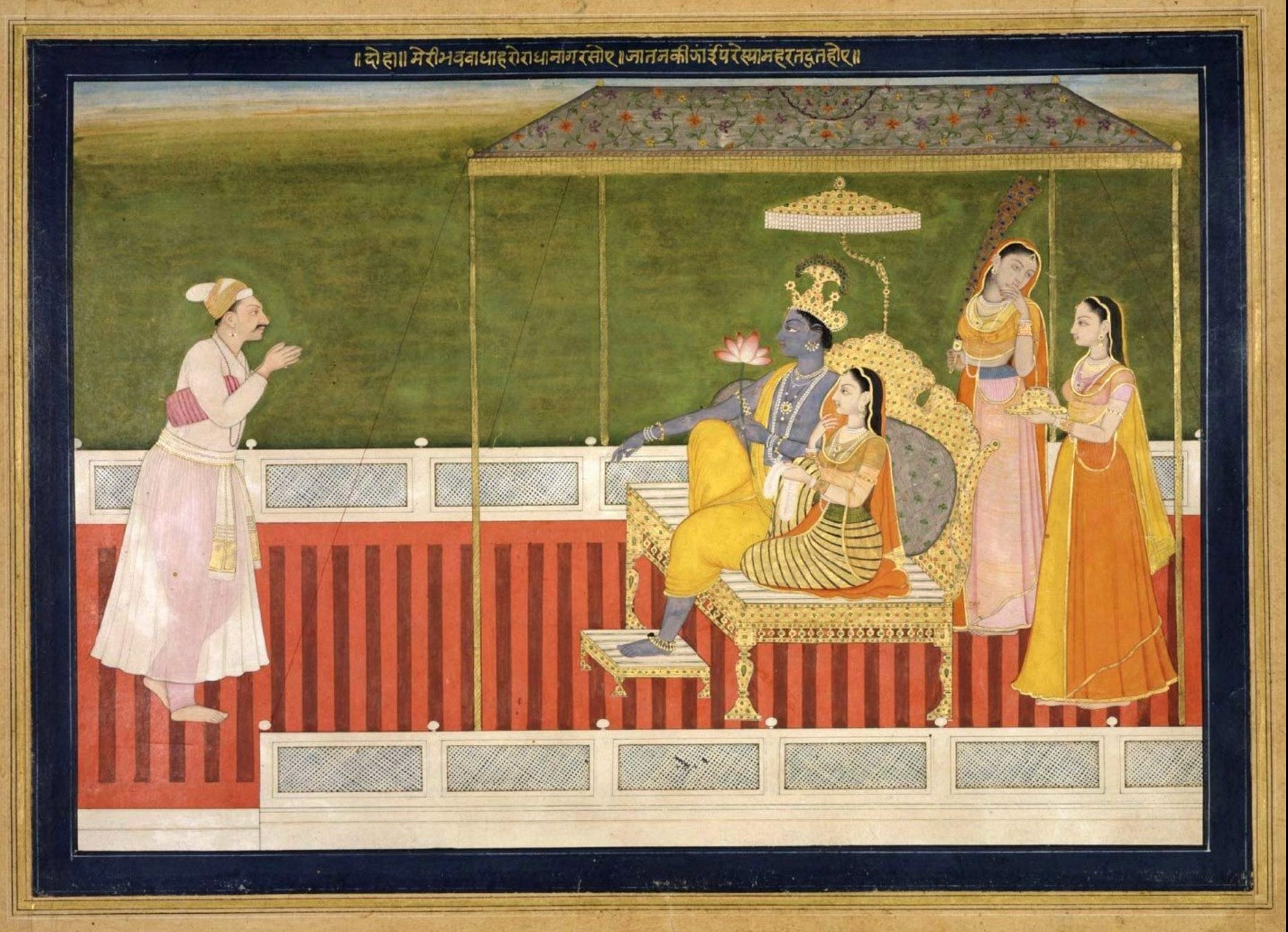

Nainsukh’s glorious art

By Hypatiaa

Fresh from Bath, by Ravi Varma

Group of Nair women photographed by Egon von Eickstedt, 1920s, Malabar.

Nainsukh’s glorious art

Hypatiaa wanders the hallways of the internet writing about culture, romance and SRK. You might have seen her on her now defunct Twitter @abbakkahypatia, or her Instagram @hypatiaa16

Share it with your friends and colleagues!